In the 2011-16 Assembly Mandate, MLAs debated, scrutinised and passed a range of legislation across a number of policy areas – from Mental Capacity to Licensing of Pavement Cafes, from Tobacco Retail to Rural Needs. When a Bill is introduced in the Assembly, it is accompanied by an Explanatory and Financial Memorandum (EFM). The EFM is essentially a guide to understanding the policy intentions and the cost of a proposed measure. But how useful are these EFMs?

Requirements for Explanatory and Financial Memoranda

The Assembly’s Standing Order 41 states:

41. Public Bills: Explanatory and Financial Memoranda

Public Bills on introduction shall be accompanied by an explanatory and financial memorandum detailing as appropriate –

(a) the nature of the issue the Bill is intended to address;

(b) the consultative process undertaken;

(c) the main options considered;

(d) the option selected and why;

(e) the cost implications of the proposal/s.

In addition to the formal requirements of Standing Order 41, the former Office of the First and deputy First Minister provided departments with guidance on the contents of the EFM.[1] In relation to finance, it states:

FINANCIAL EFFECTS OF THE BILL

This would deal with the cost implications of the proposed legislation including an estimate of public sector financial costs and of effects on public sector manpower. Where appropriate, this section should include reference to the recommendation of the Minister of Finance and Personnel under section 63 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998.

The guidance is not extensive, implying that a degree of discretion is given to departments. Nevertheless, it specifically refers to two estimates:

- Public sector financial costs. By referring to estimating ‘financial costs’, the guidance seems to suggest that the EFM need not consider wider economic costs. This means that the EFM should contemplate the resource costs that will impact on public sector budgets but need not seek to estimate any additional opportunity costs.

- Public sector manpower. This means the EFM should contemplate the impact of the Bill on public sector staffing levels. The guidance does not appear to suggest that the EFM needs to contemplate wider manpower impacts of the proposed legislation, such as on businesses, for example.

The quantity of financial information in EFMs

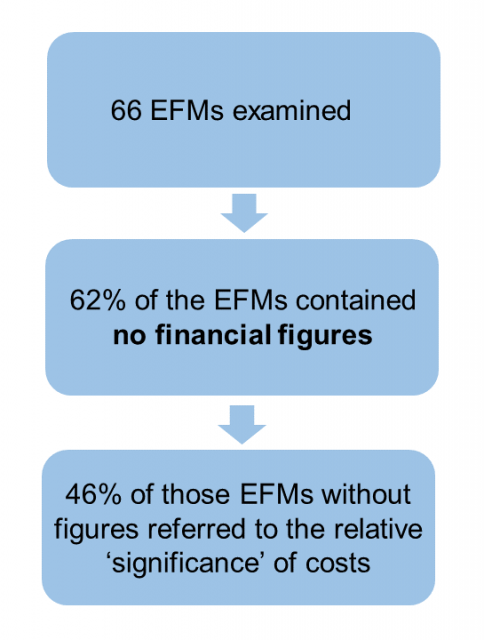

The Public Finance Scrutiny Unit within the Research and Information Service examined 66 EFMs from the 2011-16 Mandate. This sample was all the Bills introduced during the period except Budget Bills. Because Budget Bills are all about the authorisation of expenditure, they do not contain a separate statement about financial effects in the EFM.

Of the other EFMs examined, 41 of the EFMs contained no financial figures at all.

Of these,19 (46%) used said there would be no ‘significant’ financial implications arising from the Bill.

‘Significance’ is relative

Whether a cost is significant to a department is likely to depend upon the size and nature of that department’s budget. For example, a £1 million (m) resource cost to a small department like the Executive Office is clearly more significant to it than it would be to the Department of Health which has a much larger budget.

In addition, for a department with a relatively small capital budget – such as the Department of Finance – a £500,000 capital cost is more significant than to a department with a large capital budget (such as the Department for Infrastructure). This means that it is not only the size of the cost, but also the nature or category of the expenditure which contributes to its relative significance.

The quality of financial information in EFMs

It appears that where there is financial information provided in an EFM, it should not be taken as an indication that the figure is necessarily well considered or reliable. Estimates are by their very nature liable to a margin of error.

The PFSU examined a number of EFM cost estimates for accompanying both executive and non-Executive Bills introduced in 2015-16 into the Assembly for consideration. In many instances, the information provided in the EFM was of questionable value to MLAs.

For example, on 30 November 2015, the Minister of Education introduced the Addressing Bullying in Schools Bill. The objectives of the Bill were to: provide an inclusive definition of ‘bullying’; introduce a duty on the Board of Governors of each grant aided school to secure measures to prevent bullying; and, introduce a duty to keep a record of incidents of bullying.

The associated EFM contained limited information which relates mainly to designing and building a new module for an existing IT platform. But the PFSU found the Department of Education (DE) did not estimate costs for a range of areas, such as:

- training for teachers on the new system;

- training for Boards of Governors of the grant-aided schools on their new role;

- reviewing bullying prevention measures;

- the potential additional staff resources to analyse the bullying data and disseminate; or,

- DE guidance.

In another instance, the estimated costs of the Mental Capacity Bill were presented as falling within a range. But actually, the PFSU found there was a choice between two delivery options – an expensive one and a cheap one – two extremes, with nothing in between.

This was potentially important, especially because the Department of Health Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) viewed the cheaper of the options as unviable. In other words, in that case it was misleading to think of the projected costs as a range. In effect, the low-cost option was a baseline or ‘no change’ position, which did not provide a realistic or workable means of delivering the requirements of the legislation.

These two examples illustrate the considerable scope for improvement in this area in the new mandate. The inclusion of more robust and transparent information in EFMs would better serve MLAs when they debate and vote on proposed legislation.

[1] The guidance is unpublished but a copy was provided to RaISe by OFMdFM in December 2015