In 2016 the former Minister for Education, Peter Weir MLA, spoke of wanting to address composite classes, whereby a single teacher is responsible for two or more years of students at the same time. The former Minister suggested that it is more difficult for teachers to deliver high quality education in composite classes and that pupils need to be able to interact with peer groups. He stated that by the end of the planning period, he expected actions to address ‘the issue of primary pupils being taught in a composite class of more than two year groups’. This article looks at the evidence base on composite classes in Northern Ireland and around the world, considering how common they are, their educational outcomes and benefits and challenges.

How common are composite classes?

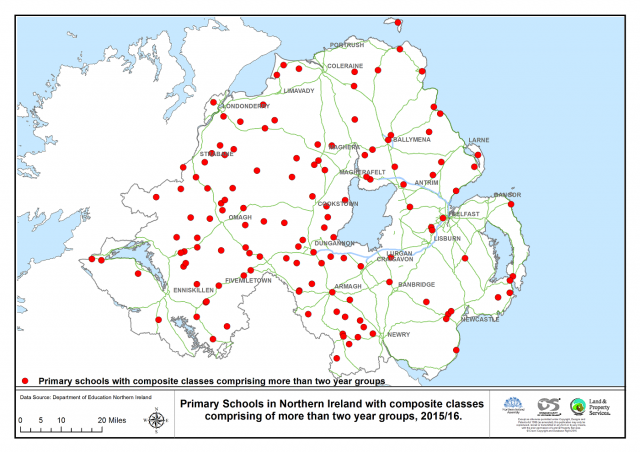

More than half of primary schools (59% or 488 primary schools) in Northern Ireland had at least one composite class in 2015/16. Most of these (87%) comprised two year groupings in a single class. The majority were in rural areas and were spread widely across Northern Ireland.

Catholic maintained schools are disproportionately represented among schools that have composite classes with more than two year groups (52% compared to 39% of controlled schools). In the wider population, Catholic maintained and controlled schools each make up around 45% of schools.

Composite classes are not unique to Northern Ireland, and have a long and established history in schools. Indeed, just under a third (30%) of the world’s children are thought to study in them.

A total of 133 primary schools in Northern Ireland have at least one composite class made up of more than two year groupings; these schools are illustrated in the Figure below.

What does the evidence say about outcomes in composite classes?

The Education and Training Inspectorate’s Chief Inspector’s Report 2014-16 stated that it is more difficult for a teacher to ensure adequate learning progression and meet all learners’ needs in composite classes spanning more than two year groups. It also suggested that such classes can limit children’s opportunities for social and emotional development with peers.

The Assembly’s Research and Information Service asked the Department of Education for Key Stage 1 and 2 assessment data in composite classes. However, it advised that it did not hold the requested information separated by composite classes. This potentially raises questions around the evidence base on composite classes.

Turning to the wider research on composite classes; although it is not strongly conclusive, generally studies have not found significant differences for student outcomes between composite and single-year classes. Some of the research points to teaching quality as a more important factor than class groupings.

There is limited evidence on the composition of multi-year classes. However, a 2014 study of schools in the Republic of Ireland found that class composition (including the number of year groups within a class) was not associated with reading or maths test scores. Research in the US supports this finding, although a large Norwegian study found that students in composite classes in lower post-primary schools performed slightly better than their peers in single-grade classes, due to sharing with more mature peers. Nonetheless, for older children sharing a class with younger children appeared to lower achievement.

Benefits and challenges

The evidence highlights a number of advantages and challenges for pupils in composite classes. The benefits include continuity, smaller class sizes, exposure to role models and more advanced materials for younger children and opportunities to revise subject content and practise leadership skills for older children.

The challenges centre around catering for a wide range of abilities within the composite classroom, such as organising the curriculum, providing high quality teaching for all, accommodating assessments and an increased workload for teachers.

There may also be challenges from a social perspective. A study from the Republic of Ireland found evidence that younger children in mixed classes with older peers tended to have a more negative view of their own abilities, and a lower perception of their own popularity, compared to their peers in single-year classrooms. This was not the case for those pupils mixed with younger children, or those mixed with both older and younger children. Findings also differed by gender, suggesting complex dynamics may be at play within composite classes.

A lack of teacher preparation

In Northern Ireland and across a number of other jurisdictions, there is a lack of focus on composite class teaching in initial teacher education and continuing professional development. Indeed, the Education Authority does not provide specific training to teachers of composite classes on teaching strategies.

What’s ahead for composite classes?

Composite classes are prevalent both in Northern Ireland and around the world. While the evidence is not strongly conclusive, research does not tend to find significant differences in educational outcomes for children educated in composite classes.

The evidence highlights a number of areas that could be considered further, such as the evidence base on composite classes and the implications of seeking to reduce composite classes with more than two year groupings from a rural proofing perspective, and given the higher representation of Catholic maintained schools.