This week sees people across Northern Ireland getting interested and involved in science through the Northern Ireland Science Festival. We thought we would join the celebration of all things scientific by taking a look at science education and skills across Northern Ireland and the impact they are having on our economy and prospects for the future.

Science at school

Back in 2015, RaISe (the Assembly’s Research and Information Service) released a research paper looking at science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education in our schools (see also a subsequent blog article on the subject). Whilst key evidence revealed there were reasons to be proud of Northern Ireland’s performance in science and mathematics compared to other countries, it also indicated significant room for improvement. Since the publication of this paper, new league tables have been published which update the performance figures in these subjects – the Trends in International Maths and Science Study (TIMSS) for primary level and the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) for age 15. So how did Northern Ireland do this time around, and how does it compare to past performance?

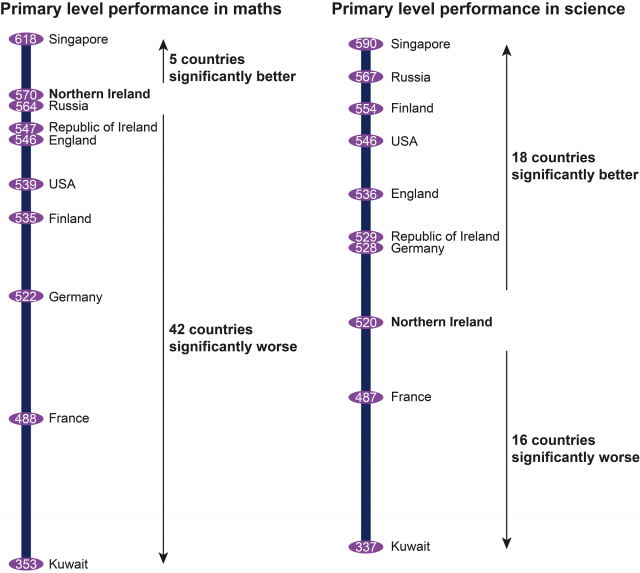

The 2011 TIMSS study of science and maths performance at primary school level showed that during that year Northern Ireland was punching above its weight in maths; performing better than 44 of the 49 countries examined, including England, the Republic of Ireland and Finland. In 2015, TIMSS findings revealed that this continued to be the case, with Northern Ireland’s performance ranking sixth amongst the 42 countries compared that year. This placed Northern Ireland behind the leading countries such as Singapore and South Korea, but significantly ahead of others for example, the Republic of Ireland and England – and on par with Russia.

Northern Ireland’s 2011 performance in primary level science was not quite as good as in maths; a trend which continued in 2015. In 2011, 17 countries had performed significantly better than Northern Ireland in science, which then rose to 18 countries in 2015. For both years Northern Ireland had performed worse than England, and not significantly different from the Republic of Ireland.

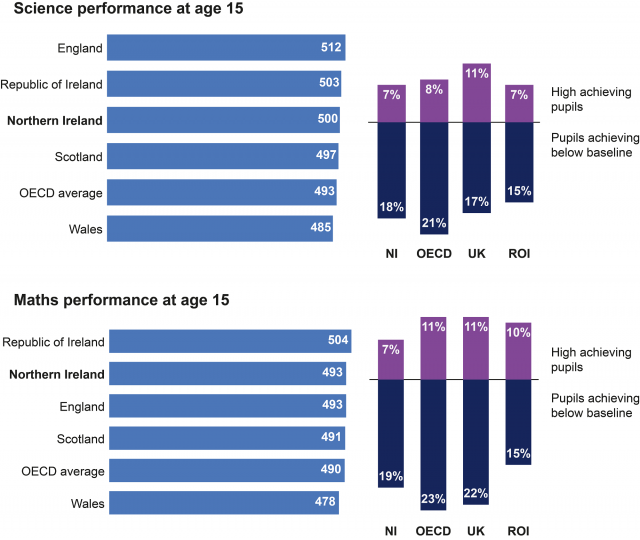

Whilst TIMSS showed Northern Ireland’s primary level performance in 2011 was comparably good, the PISA study in 2012 revealed its performance was not as strong for those aged 15. The 2012 study showed Northern Ireland’s age 15 performance in science was in line with the OECD’s (Organisation of Economic and Social Development) average, but performance in maths was significantly below the OECD’s average, despite Northern Ireland’s strong primary level performance in maths.

However, the updated 2015 PISA study showed improvement for Northern Ireland on both these fronts. Performance in maths for those aged 15 went from significantly below the OECD average, to about average, whilst performance in science for that age group went from average to significantly above the OECD average.

Moreover, performance spread showed Northern Ireland’s proportions of high and low achievers in science at age 15 were broadly similar to the OECD average. This marked a decline from 2012 when Northern Ireland had a greater proportion of high achievers in science than average. In maths, the proportions of high and low achievers in 2015 for those aged 15 were both below the OECD averages. These figures raise questions of how Northern Ireland can increase its proportion of high achieving pupils in both maths and science.

Science skills for work

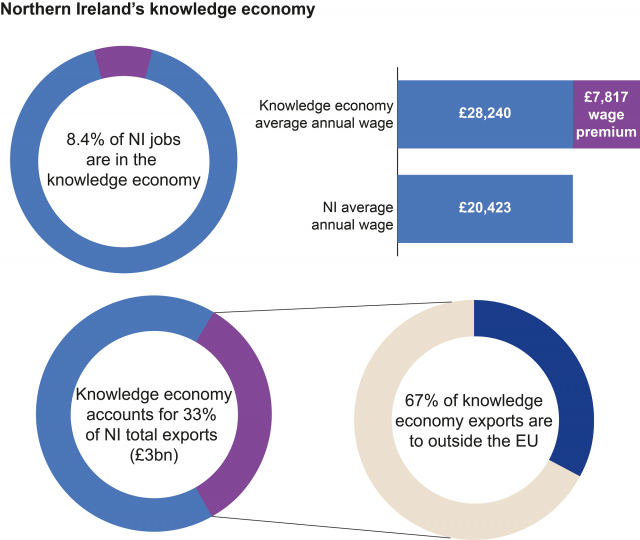

In the coming years, science is expected to make an increasing contribution to the Northern Ireland economy. Science and technology jobs make up most of what has been termed the “knowledge economy”. As of 2015 they had provided 72,000 direct, indirect and induced jobs in Northern Ireland; that is about 1 in 12 of all people employed in Northern Ireland. These jobs have tended to be high-paying jobs, approximately £8,000 above the Northern Ireland average annual wage. Overall this sector brings in £3billion in exports (33% of total Northern Ireland exports), with 67% going outside the European Union; potentially making this sector especially important in the context of Brexit.

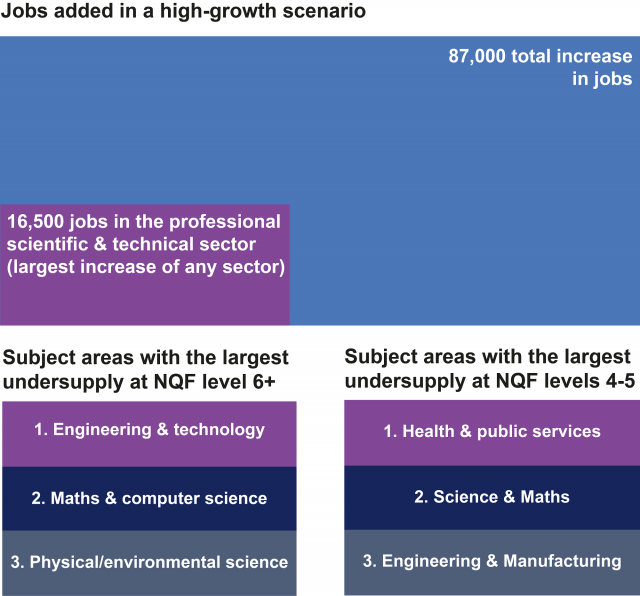

The sector’s apparent significance is evidenced by findings recorded in the 2017 Northern Ireland Skills Barometer Report. That Report indicated that employment in professional scientific and technical work will see the biggest increase over the next 10 years in a high growth scenario. However, it also showed Northern Ireland is significantly undersupplied in the science and other STEM-related subjects that the evolving economy will need in the coming years.

The Skills Barometer Report showed that demand for skilled workers with qualifications of A-level or above will be severely undersupplied, and that the undersupply falls primarily in science-related subject areas. It indicated that at graduate and post-graduate level the three subjects with the biggest under-supply are: Engineering & Technology; Maths & Computer Science; and Physical/Environmental Science. It added that the same can be said for skills needed at the foundation degree or equivalent level; skills in health; science and maths; and engineering and manufacturing are all stated to be the most significantly under-supplied. This is despite the fact that the enthusiasm to work in science-related fields exists, as evidenced by the PISA study findings, which indicated about one-third of 15-year-olds in Northern Ireland in 2012 and 2015 expected to work in science-related professions at age 30. Such expectation was significantly more than the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland or OECD average.

What next?

At school level, Northern Ireland continues to achieve good results in maths and science, with the already respectable performance at primary level holding steady and the weaker performances at age 15 when compared to the OECD average having improved. It will be important for Northern Ireland to ask how it can build on this and continue to improve school-level maths and science performance, and in particular, how to increase the number of high achieving pupils in both subjects.

Nonetheless the positives at school level are apparently not translating into the skills needed for work: shortages in science and technology skills exist at a range of levels. The Skills Barometer Report noted that this challenge is shared in many developed economies. Perhaps Northern Ireland could learn valuable lessons from those other economies as it faces such challenges, particularly given the sector’s large and growing contribution to the Northern Ireland economy and the high quality of the jobs that the sector produces.