This blog article is the first in a series of two which discusses the issue of marine plastic waste in Northern Ireland (NI), based on a research paper published recently by the NI Assembly Research and Information Service (RaISe). In this first article, we outline the current state of knowledge regarding the scale of plastic waste in the marine environment here in NI, discuss potential environmental, economic and societal impacts, and examine where this plastic waste is coming from in terms of both geography and industry. In part two, we will explore current policy in place to tackle marine plastic waste in NI, and potential options for the future drawn from current UK-wide proposals and strategies adopted elsewhere.

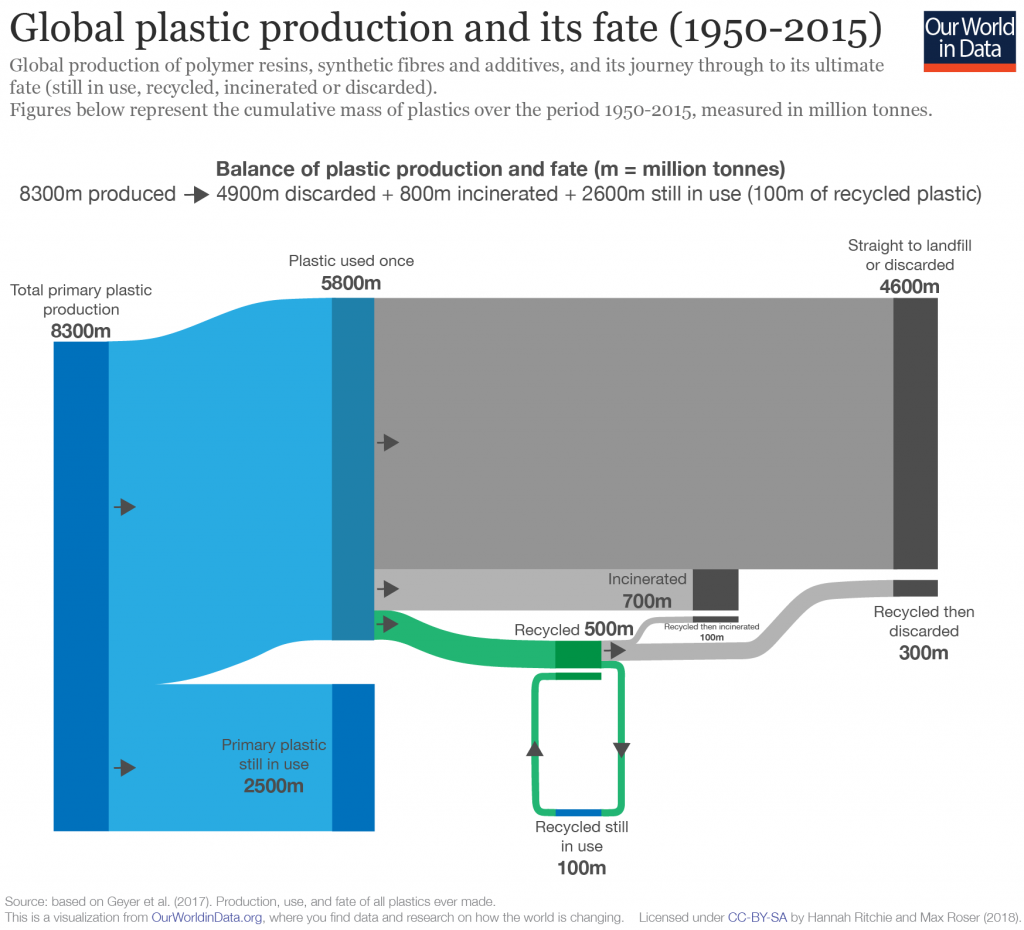

Plastics are useful materials, not least for their extreme durability. Whilst a beneficial property for common applications such as packaging, this means that plastics can take hundreds to thousands of years to degrade, making them effectively permanent unless recycled or incinerated. Since large scale plastic production began in the 1950s, over 8 billion tonnes of new plastics have been manufactured globally, over half of which has ended its life discarded in landfill or the environment. Of the plastic waste we produce, a sizable quantity ultimately enters the seas. The scale of plastic waste in the marine environment is an issue subject to increasing public awareness.

The situation in Northern Ireland

With over 330 miles of coastline, the condition of the local marine environment in Northern Ireland is of major significance. The coast is a key asset supporting tourism and recreation, sea fisheries and local wildlife. An abundance of plastic pollution has the potential to damage any one of these.

Plastic litter is the most common type of litter found on beaches in NI. Since 2012, environmental charity Keep Northern Ireland Beautiful (KNIB), with support from the Department of the Environment (DOE) and latterly the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA), has carried out regular beach litter surveys across ten beaches along the coast. In most recent published data from 2017, KNIB reports finding an average of 358 plastic items for every 100m of beach walked. The most commonly recorded litter items in 2017 were plastic and polystyrene pieces; plastic string, cord and rope; plastic drinks containers; and plastic drinks caps and lids.

Offshore, plastic items have been recorded on the seafloor in bottom trawl surveys off the north and east coast of NI. Quantities of plastics found in these surveys are variable, up to 60 items per trawl, but many return only one or two. Whilst this variability could be due to local variation in the rate of plastic pollution, other factors are also likely at play.

Variation in the quantity of plastics in different locations offshore is related to the way in which currents carry and redistribute plastics globally. The mobility of plastics at sea means that some of the plastics found in the waters around NI may not have a local origin, and also that Northern Ireland is likely to be responsible for some of the plastic pollution found in other corners of the world. Simulations of ocean currents by the Grantham Institute, Imperial College London, predict that most floating plastics released from the shores of the UK ultimately reach the Arctic within 20 years.

Impacts of plastic debris at sea

Plastics may be abundant in the oceans and documented locally within waters around Northern Ireland, but do they do any harm?

Perhaps the highest profile impact of plastic pollution is the harm it can inflict on marine wildlife. Marine animals can become entangled in debris – discarded synthetic fishing nets being a particularly common culprit – leading to physical injury and possible starvation. Incidents of entanglement between marine wildlife and plastic debris have been documented in over 250 species worldwide including mammals, birds, fish and turtles.

Plastic ingestion by wildlife is also observed frequently and has been recorded in around 300 species. The presence of plastics in the digestive tract is extremely widespread in many organisms – a 2019 study examined the guts of 50 marine mammals stranded on the coast around Great Britain and found plastics in every one. Yet, whilst the ingestion of large plastic items can cause clear damage to the digestive tract, much of the plastic consumption of wildlife involves tiny fragments of plastics (termed ‘microplastics’ when less than 5mm). The extent to which the ingestion of microplastics causes harm, particularly in larger animals where they are unlikely to cause internal injuries or blockages, is still uncertain.

Plastic ingestion may also be significant for commercially important species. Fisheries in NI are particularly reliant upon the harvesting of Nephrops (also known as prawn, scampi or langoustine), which made up 33% of the total catch and 50% of the commercial value of landings in 2017. In research from the Clyde Sea off the coast of Scotland (less than 100km from the coast of Northern Ireland), 83% of Nephrops caught contained microplastics in their digestive tract (mostly plastic fibres). Under experimental conditions it was then shown that microplastic ingestion of the level observed in the wild could have starvation-like effects on body condition. If similar levels of microplastic exposure are present in waters around NI, this may be of local concern.

If plastics are being consumed by commercial species, what does this mean for human health? Reports from both the UK Government’s Chief Medical Officer and the United Nations Environment Programme conclude that there is currently no evidence of negative human health impacts, although both note that significant knowledge gaps remain. For most species we consume, the gut (where plastics accumulate) is removed before consumption. For species consumed whole, it is unclear to what extent plastic exposure through diet poses a major threat, when compared to the level of exposure to plastic fragments encountered in day-to-day life.

Marine plastics could also incur economic costs, through impacts on fisheries, tourism and clean-up costs. Research from Scottish fisheries in 2010 estimated losses of between €17,219 and €19,165 per vessel per year as a result of debris (of all materials) at sea, mainly attributable to the time spent clearing nets of tangled litter. Litter can also impact use of the sea and nearby areas as destinations for tourism and recreation and litter is often cited as a key reason preventing visits to coastal sites. Reduced visitation could impact tourism revenues, and the process of cleaning up litter can incur significant costs to charities and local authorities. In addition, current research suggests that visits to coastal sites can be beneficial for health and wellbeing, particularly in terms of mental health and physical activity. An abundance of plastic pollution in coastal locations has the potential to reduce these benefits.

Where is it coming from?

If plastic waste in the sea is to be reduced, it is important first to understand where it is coming from. Plastics which reach the sea can be categorised according to whether they have a land- or sea-based origin. Land-based sources include coastal litter; illegal dumps; waste water and storm water discharge; and industrial activities. These can contribute to marine debris once items are washed into watercourses, or once waste water is discharged out to sea. At sea, the loss or discarding of fishing gear (often made of synthetic fibres), shipping, offshore industries and direct dumping from vessels can all release plastics into the water.

Of the plastic found in marine environments, much of it is identifiable as packaging. Around a quarter of plastic items found on beaches in Northern Ireland between 2012 and 2017 were related to food packaging, and many more were plastic fragments which could once have come from a packaging item. A further quarter of items were linked to fishing: plastic string and cord, nets and recreational fishing gear.

So how much of the plastic we find in oceans comes from the land and how much from the sea? Whilst it is widely cited across reports on marine litter that 80% of marine plastic waste had a land-based source, the origins of this figure are unclear. A 2015 report from the European Environment Agency concluded that land- and sea-based sources are equally significant in the North East Atlantic sea region (which incorporates the Northern Ireland coast). Data from the European Commission state that 60% of all plastic beach litter items in Europe are single-use plastics (presumably from a land-based source), and a third are made up of fishing items. Whilst precise figures for the relative contributions of land- and sea-based sources vary, it seems clear that both make substantial contributions to total marine plastic debris.

Upon first inspection, analysis of contributions of marine plastic waste by country appears to show that the UK as a whole is not amongst the greatest contributors globally. However, this figure could misrepresent our true contribution to plastic pollution globally. Research has shown that just twenty countries[1] account for 80% of global marine plastic pollution, the majority of which comes from a key hotspot in south east Asia. It is important to note, however, that the UK exports a substantial proportion of its plastic recycling waste abroad (63% of plastics collected for recycling in 2018), often to those countries with poor records of waste management. This means that it is possible that the UK could be offsetting its environmental impact thousands of miles away. Indeed, a recent BBC programme highlighted the impact of plastic waste from the UK being processed in Malaysia. A number of these countries have recently imposed high-profile bans or restrictions on imports of waste plastic and in Westminster Defra has expressed interest in processing more plastic waste at home. The extent to which this will increase investment in local recycling facilities here in NI is not yet clear.

In part two of this blog article, we will explore the current policy framework for addressing marine plastic waste in NI, recent proposals for UK-wide action, and discuss additional approaches from across the UK and further afield.

________________

[1] In order, these countries are: China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Egypt, Malaysia, Nigeria, Bangladesh, South Africa, India, Algeria, Turkey, Pakistan, Brazil, Burma, Morocco, North Korea and the United States.