The recent New Decade, New Approach deal to restore power-sharing in Northern Ireland contains considerable commitments to financial support but scant detail. A release by the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) on 15 January provided some more information. Yet confusion and controversy continue to surround this issue, with the new Minister of Finance describing the package as ‘woefully inadequate’ and an ‘act of bad faith’.

This blog article does not enter that debate. Instead, it investigates further an issue that has received a little less attention: the establishment of an Independent Fiscal Council for Northern Ireland (IFCNI).

What does the Agreement say about the proposed IFCNI?

The Agreement states:

An independent Fiscal Council will be established in Northern Ireland by July 2020. As per the Fresh Start Agreement, the membership and terms of reference of this Council will be agreed with the UK Government. It would:

- prepare an annual assessment of the Executive’s revenue streams and spending proposals and how these allow the Executive to balance their budget; and

- prepare a further annual report on the sustainability of the Executive’s public finances, including the implications of spending policy and the effectiveness of long-term efficiency measures; and

- have its membership and terms of reference agreed with the UK Government.

Elsewhere in the document, it states that the IFCNI:

…will provide independent monitoring and reporting on the Executive’s performance in delivering the Programme for Government.

So, it appears that the IFCNI will be expected to do more than advise on money matters. It will review the Executive’s performance on delivering its stated objectives.

Is this a new idea?

In November 2015, the Fresh Start Agreement stated:

The UK Government welcomes the Executive’s plans to establish an Independent Fiscal Council for Northern Ireland. The Council will:

- prepare an annual assessment of the Executive’s revenue streams and spending proposals and how these allow the Executive to balance their budget; and

- prepare a further annual report on the sustainability of the Executive’s public finances, including the implications of spending policy and the effectiveness of long-term efficiency measures.

The 2015 proposal is similar with regard to assessment of financial sustainability, but does not mention performance monitoring.

Do similar bodies exist elsewhere?

Internationally, there are many bodies which resemble the proposed IFCNI, although their names vary: there are ‘fiscal commissions’, ‘offices of budget responsibility’, and ‘parliamentary budget offices’. Collectively, these are known as Independent Fiscal Institutions (IFIs). Across the member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) IFIs vary considerably in design and remit: there is no one-size-fits-all model.

In general, IFIs are public institutions with mandates to critically assess (and in some cases provide non-partisan advice on) the government’s fiscal policy and performance. Whatever they are called, a key point is that IFIs are independent of the Executive arm of government. Sometimes they are established by the legislature (like the Parliamentary Budget Office in Canada).

Some IFIs (such as the UK Office of Budget Responsibility) prepare their own macroeconomic and fiscal forecasts. Others (such as the High Council of Public Finance in France) assess those prepared by finance ministries for the Executive. Some evaluate governments’ fiscal plans and outcomes. Unlike audit institutions (such as the Northern Ireland Audit Office), which look back into governments’ activities, IFIs are usually, but not always, forward looking in their analysis.

Why have an IFI?

The OECD argues that IFIs can help,

address biases towards spending and deficits, […] foster greater transparency and accountability […] and enrich public debate.[1]

By doing so, they can promote sound fiscal policy and the sustainability of public finances. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), IFIs can promote stronger fiscal discipline ‘as long as they are well-designed’. Ultimately, there is a range of reasons why an IFI might be established. To illustrate:

- The UK Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) was set up after the 2008-09 credit crisis ‘to build credibility and foster trust in the integrity and sustainability of the public finances‘;

- The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) provides, among other things, ‘written estimates of the cost of virtually every bill approved by Congressional committees to show how the bill would affect spending or revenues over the next 5 or 10 years‘; and,

- The South Korean National Assembly Budget Office (NABO) analyses the annual budget bill and makes suggestions both for increases or decreases in allocations, and for policy improvements.[2]

IFI proliferation

Some IFIs have been in place for a long time. For example, the Belgian High Council of Finance was established in 1936, although it has been reformed over the years. Other long-established IFIs include the Netherlands (1945), Denmark (1962), Austria (1970) and the United States (1974).

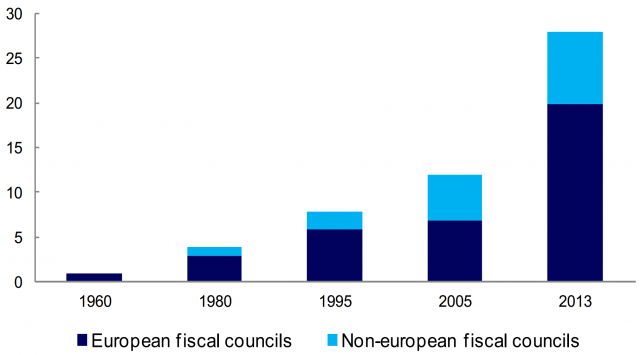

Since 2008, the number of IFIs within OECD member countries has more than tripled, with impetus given by the surge of government deficits and debts in the 2008-09 credit crisis. Policymakers aimed to use IFIs to safeguard fiscal discipline and to rebuild public trust in government budgeting.

On 30 January 2012, the Eurozone Member States committed to a ‘fiscal pact’, which says a government’s structural deficit is to be capped at 0.5 per cent of its gross domestic product. A breach of this ceiling triggers automatic correction mechanisms.

Among other things, the Treaty On Stability, Coordination And Governance, and related implementing regulations, required signatory countries to establish institutions to monitor compliance with the ‘fiscal pact’. These institutions are IFIs, and must be independent of Member States’ budgetary authorities (i.e. Ministries of Finance or equivalent). This EU-level action contributed significantly to the growth in IFIs, as shown in Figure 1.

Ireland has not one, but two IFIs:

- The Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, established in 2011 to provide an independent assessment of official budgetary forecasts and proposed fiscal policy objectives; and,

- The Parliamentary Budget Office, established in 2017 to provide independent and impartial information, analysis and advice to the Houses of the Oireachtas.

Sub-national IFIs

In addition to the growth in number of IFIs at the national level, a more recent development is the sub-national IFI. Examples include the Scottish Fiscal Commission, and in Canada the Financial Accountability Officer in Ontario, and the Victorian Parliamentary Budget Office in Australia. In Wales, the sub-national IFI role is actually fulfilled by the national Office of Budget Responsibility.

Similar to national IFIs, there is no one-size-fits-all model for a sub-national IFI. Based on OECD information, it is clear they can be based in the legislature, like in Victoria, or be more like a fiscal council, like in Scotland.

From the limited information available to date, it appears the IFCNI will end up looking like more like a fiscal council than a legislative budget office. Ultimately, the remit of the IFCNI will relate to the devolved fiscal powers of the Executive. Under the current devolved financial arrangements, the Executive is responsible for setting the Regional Rate (a property tax) and certain elements of Air Passenger Duty. From April 2018, it was to assume the power to set a Northern Ireland rate of Corporation Tax. (For further discussion of the devolution of Corporation Tax, see RaISe’s 2015 paper Corporation Tax (Northern Ireland) Bill: Key Provisions and Considerations).

These fiscal powers may of course change in the future. Indeed, commentators have questioned whether the appetite to cut corporation tax remains. Irrespective of that, as things stand, devolved fiscal powers are much more limited than in Scotland and Wales. This may imply a relatively limited remit for the IFCNI.

Considerations for the IFCNI’s design

In 2014, the OECD published principles for the design of IFIs. Based on lessons learned and good practices, these cover a range of issues, such as the need for local ownership:

Local needs and the local institutional environment should determine options for the role and structure of the IFI.

And independence and non-partisanship:

Non-partisanship and independence are pre-requisites for a successful IFI.

In addition, in 2013, the IMF published a study on the functions and impact of IFIs. This identified the following key features:

…a strict operational independence from politics, the provision or public assessment of budgetary forecasts, a strong presence in the public debate (notably through an effective communication strategy), and an explicit role in monitoring fiscal policy rules.

Taken together, these principles and findings, as well as several helpful case studies published by the OECD, will enable interested parties, including MLAs and others, to consider and assess the proposals made for the IFCNI when they emerge.

_____________________________________________________

[1]OECD Journal on Budgeting, 2015 Volume 2 Issue 2 ‘Principles for independent fiscal institutions and case studies’ (page 11)

[2]Kwangmook Kim (2016) Presentation at the Annual Meeting of OECD Parliamentary Budget Officials & Independent Fiscal Institutions, Paris, 11 April 2016