The recently appointed UK Chancellor presented his first Budget on Wednesday (as had been planned by his predecessor). It was announced in place of the cancelled Autumn Budget, which was due to be delivered at the end of 2019. The timing here is problematic for the Northern Ireland (NI) Executive because the Chancellor’s Budget overwhelmingly determines the UK-level of resources that will be available to NI for budget year 2020-21 (starting in only a couple of weeks’ time).

Longer-term resourcing from the UK Government will be the subject of its Spending Review, which is scheduled to occur this summer. But for now, the Chancellor’s Budget finalises Whitehall-level departmental allocations for 2020-21. The amount of those allocations then will inform the majority of funding that will be available to NI for 2020-21 from the UK Government, which was primarily determined by applying the Barnett Formula. Other funding will be determined by the Executive via the future Regional Rate, which is raised locally from domestic and non-domestic property owners (and currently under Department of Finance’s review).

This blog article describes the context for Wednesday’s budget, and outlines a number of key measures and their implications for Northern Ireland.

The context for UK Budget 2020

According to Civil Service World, the Chancellor had to do a re-write of the Budget to ‘take account of the likely economic effect of the Covid-19 outbreak’. This included the addition of extra cash for the NHS and other public services, to help them cope with the impact of a major rise in confirmed cases in the UK.

The fiscal impact of the viral pandemic

Concerns about the spread of the virus formed a significant part of the backdrop to the Chancellor’s Budget 2020. For one thing, the coronavirus is impacting on the economy. For example, the Ulster Bank Ireland’s February Construction Index noted that the global spread of the coronavirus represents a source of downside risk to the economy, particularly to ‘the more heavily trade- and tourism-dependent areas of the economy’.

The scale and speed of further spread of the virus is clearly unknown, and that makes policymaking more difficult. The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) recently advised that the economic policy focus should be:

The key focus of an economic policy response should be to ensure continued delivery of public services and to minimise the long-term effects of what will hopefully be a short-term increase in levels of illness.

The IFS went on to identify that the priorities should be:

- Supporting affected businesses to help prevent this largely short term event having long term ‘scarring’ effects;

- Supporting individuals who lose income;

- Ensuring the delivery of public services.

The Chancellor’s Budget 2020 announced a variety of fiscal and other policy measures in a three-point plan to provide support for:

- Public services – including an initial £5 billion ‘Emergency Response Fund’, funding for research and development and increasing the capacity for diagnostic testing;

- Individuals – including Statutory Sick Pay (SSP) to be paid from the first day of absence, including those who have to self-isolate, (which changes the requirement for a ‘fit note’ from GPs for absences related to the pandemic), welfare system support for those who cannot access SSP, and a ‘Hardship Fund’;

- Businesses – including support for Small and Medium-Sized businesses and employers to cope with the extra costs of paying COVID-19 related costs, such as Business Rates Relief, a temporary ‘Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme’, and a dedicated helpline for advice regarding deferral period for tax liabilities.

In addition to decisions made in the Treasury, The Bank of England has a role to play.

The Bank of England

The Bank of England’s remit is to independently focus on only monetary policy. On 10 March, it announced a number of measures, coordinated with the Treasury, to help address implications arising from coronavirus. Its Governor stated that the measures are to assist: ‘UK businesses and households [to] manage through an economic shock that could prove sharp and large, but [they] should be temporary’.

The Bank’s three policy committees’ actions are designed to help support both business and consumer confidence at this difficult time, in order to bolster the cash flows of businesses and households, and to reduce the cost, and to improve the availability, of finance. Those measures include cutting interest rates, and incentives for Small and Medium Sized enterprises. In addition, they are to support banks, so that they can continue to lend to businesses and households, while absorbing the effects of substantial economic disruption.

In addition to the pandemic considerations noted above, the Chancellor had other fiscal matters to think about.

Other fiscal considerations

A number of other systemic issues and related planning have been considered by the Chancellor and others for some time. For example, the Institute for Government (IfG) identified six:

- The UK economic outlook – UK growth has been weak for some time, and it is likely it will become weaker because of the pandemic. Low growth constrained the Chancellor’s options for more spending or tax cutting.

- Fiscal rules – The Budget 2020 described the fiscal rules as ensuring:

…the government is only borrowing to invest over the medium term, with the current budget in surplus, and that limits public sector net investment to an average of 3% of GDP, to keep control of borrowing and debt.

The IfG notes that fiscal-rule setting has been a feature of UK Government’s policies since 1997 and UK governments ‘have applied fiscal rules almost continuously, though many have been breached or abandoned at one time or another’. In this context, however, it is worth noting that the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) described the current fiscal rules as ‘materially looser’ than the austere rules of recent UK Governments.

This notwithstanding, the Chancellor’s Budget 2020 states:

To ensure the fiscal framework remains appropriate for the current macroeconomic environment HM Treasury will undertake a review over the summer and announce any changes by Autumn Budget 2020.

This sentence has been interpreted by some commentators as hinting at ‘a coming change’ in fiscal policy.

- Taxation – There were only two options open to the Chancellor to fund more on public services: more borrowing; or, higher taxes. As noted, circumstances are difficult in recent times, and therefore PricewaterhouseCoopers noted: ‘the new Chancellor has put substantial reforms to the personal tax system on ice and instead focused his attention on trying to improve the health and wealth of the population’.

- Brexit – Many expect a Brexit dividend in terms of the contribution that will no longer be paid to the EU. It is worth noting, however, that the OBR estimates the so-called ‘divorce bill’ to settle the UK’s share of EU staff pension liabilities, for example, at around £40 billion.

- Spending Review – This is to follow the one-year ‘stop-gap’ Spending Round in September 2019 (see the Raise blog article Northern Ireland public finances: An update for more information); a longer term UK-level expenditure plan is required. The Chancellor announced that a Comprehensive Spending Review will conclude in July 2020. It will set out detailed spending plans for public services and investment, covering resource budgets for three years from 2021-22 to 2023-24 and capital budgets up to 2024-25.

- Fuel duty – The duty on petrol and diesel is officially due to rise in line with inflation. However, the Chancellor, like his predecessors, was under pressure to cancel future increases and extend the lengthy period of freezing fuel duty and announced, ‘The government is also helping people with the cost of living by freezing fuel duty for the tenth consecutive year.’ The budget document states that the cost of freezing fuel duty for 2020-21 is £525 million for the next budget year, rising to £560 million.

In addition to the considerations identified by the IfG, some other issues which are of interest to Northern Ireland are discussed below.

Corporation Tax

The Corporation Tax (Northern Ireland) Act 2015 was enacted, but not commenced. To do so requires the enactment of a Statutory Instrument in the UK Parliament.

It is important to understand how interconnected tax issues are: changes in tax levels can lead to behavioural responses, and these are sometimes unintended and/or unexpected. The OBR has noted that any reduction to the Northern Ireland rate of Corporation Tax would have: ‘important behavioural effects that would need to be taken into account in order to estimate how much our UK-wide receipts forecast would be affected’.

There was cross-party support for a reduction in Corporation Tax in Northern Ireland at January 2017. But now the difference between Corporation Tax rates in the UK and Republic of Ireland (RoI) is smaller than it was in 2011, so its potency may be impacted. Having said this, it was widely expected that headline (i.e. the main) Corporation Tax rate would be reduced to 17% for 2020. But the Chancellor announced on Wednesday that the headline Corporation Tax rate will remain at 19%. It took many years for the Executive to get the power devolved. It is now perhaps open to question whether it will ever be exercised.

The Chancellor also announced some other issues.

Other issues

- The UK’s economics and finance ministry, Treasury, will establish representation in all the nations of the UK, building on its existing presence in Scotland, with new positions based in Northern Ireland and Wales for the first time.

- The Chancellor announced a review of the Treasury’s Green Book. This is likely to indirectly impact Northern Ireland’s own guidance regarding economic appraisal, which is currently based on ‘broadly similar principles‘ to the Treasury guidance.

Various tax measures

- Non-UK resident Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) surcharge – The government will introduce a 2% SDLT surcharge on non-UK residents purchasing residential property in England and Northern Ireland from 1 April 2021.

- In addition to freezing fuel as mentioned above, the UK Government is freezing all alcohol duties, applying a zero rate of VAT to e-publications, and abolishing the tampon tax.

It is not just the substance of the Chancellor’s Budget that will affect Northern Ireland. Timing is also an issue.

Impact of the timing of UK fiscal events on timing of the forthcoming Executive Budget 2020-21

As noted above, the Chancellor’s Budget 2020 is in place of the cancelled Autumn Budget, which was due to be delivered at the end of 2019. Budget 2020 finalises the UK-level of funding available to NI in the short-term. But this is coming very late in the budget year – the start of the 2020-21 year is only a few weeks away.

This has added to the complexity of the Executive’s budgetary planning processes. Politicians in Scotland complained that they had to set their own budget in the dark:

The Scottish government was forced to use promises made in the Conservative manifesto to attempt predictions as to how much was coming to Scotland, Ms Forbes revealed during her budget announcement.

Uncertainty in the budget planning process in Northern Ireland for 2020-2021 was underlined when the Department of Finance published a factsheet indicating that approximately £1 billion of the financial package supporting the ’New Decade New Approach’ agreement consisted of future Barnett consequentials over ‘unspecified time’, and that it was ‘unclear’, if it would be Resource or Capital.

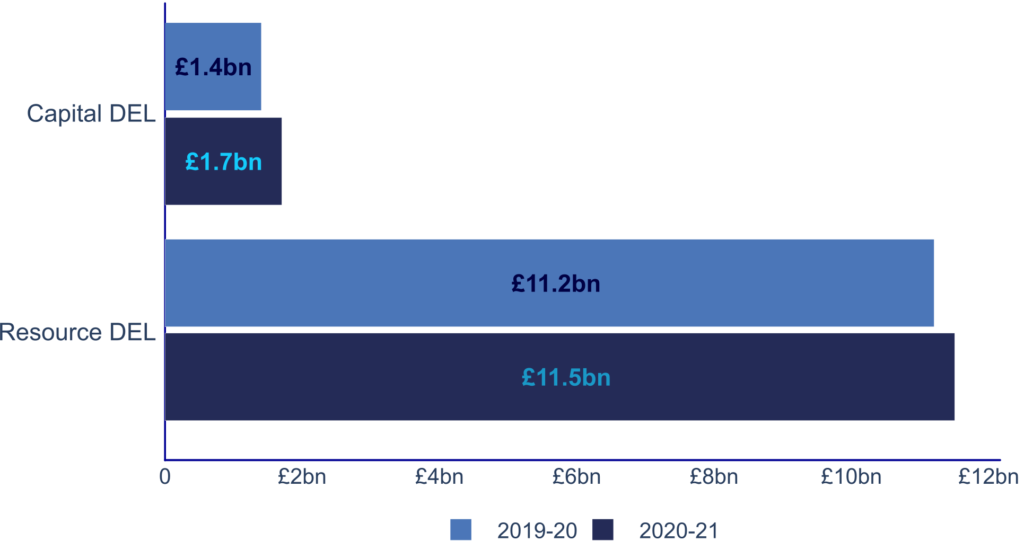

We now know that the funding allocated for 2020-21 is shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Total NI DEL 2019-20 and 2020-21 (source Budget 2020)

The chart shows an increase of approximately £600 million for Northern Ireland for 2020-21, compared to the current budget year. However, the UK Government’s Spending Round 2019 had already announced an additional £400 million for Northern Ireland. The Chancellor’s Budget 2020 announced that ‘the Northern Ireland Executive’s block grant will increase by over £210 million through to 2020-21’.

It is noticeable in Figure 1 that the larger proportionate increase is in Capital Departmental Expenditure Limit – i.e. funding for investment in assets, not day-to-day spending.

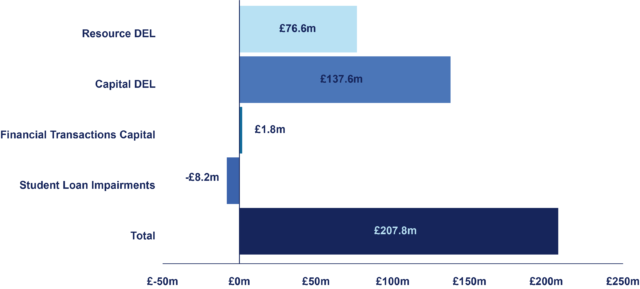

Figure 2 further illustrates this fact by showing the breakdown of the additional £210 million (m) announced on Wednesday, relying on figures provided by the Department of Finance.

Figure 2: Breakdown in changes to NI DEL

Now that the Chancellor has delivered his Budget, many in Northern Ireland are awaiting the Executive’s spending plans for 2020-21 with great interest.

Save