When the UK Government became the world’s first major economy to legislate for a ‘net zero’ target for carbon emissions by 2050, it acknowledged it would not succeed unless fundamental changes occur in the way people and goods are transported.

Moving from a car dependent society to one which makes more use of public transport, alongside walking and cycling for short trips will be essential for achieving net zero. The role of this behavioural change will be discussed in a forthcoming blog. However, given the reliance on cars in Northern Ireland (NI) this first article will look at the policy driving us towards ultra low emission vehicles (ULEV).

Towards Net Zero

The countdown has started. The UK Government has legislated to bring all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to net zero by 2050. Northern Ireland will have to make a significant contribution to this, though as a region, it will not necessarily have to reach net zero in the same time frame.

According to the body that advises Government on climate change issues, the Committee for Climate Change (CCC), an 82% reduction in all GHG in Northern Ireland represents equivalent effort and a fair contribution to the UK Net Zero target. The Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) is considering responses to a consultation that will inform a decision about how ambitious Northern Ireland should be in this regard.

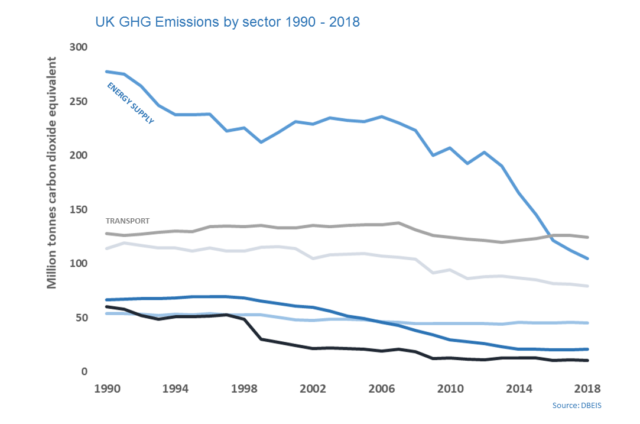

Total UK GHG emissions have been trending downwards, falling by 41% since 1990. The Energy supply sector has performed particularly well, with the phasing out of fossil fuels and increasing the use of renewables as key factors. Transport, on the other hand, has proven much more difficult to decarbonise than other sectors with emissions only 3% lower than in 1990.

The challenge

Transport was responsible for almost 28% of the UK’s GHG emissions in 2018 (the year for which the latest figures are available). Within the transport sector road transport is the largest emitter of GHG, with cars the main source. These emissions contain other harmful products such as particulate matter, carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides, which also contribute to air pollution.

The challenge is straightforward, if the UK is to achieve its net zero target, emissions from the transport sector will need to be significantly reduced. Indeed the Department for Transport has stated ‘there is no plausible path to net zero without major transport emissions reductions, reductions that need to start being delivered soon.’ This will require fundamental changes to the way people and goods move around.

Ultra Low Emission Vehicles

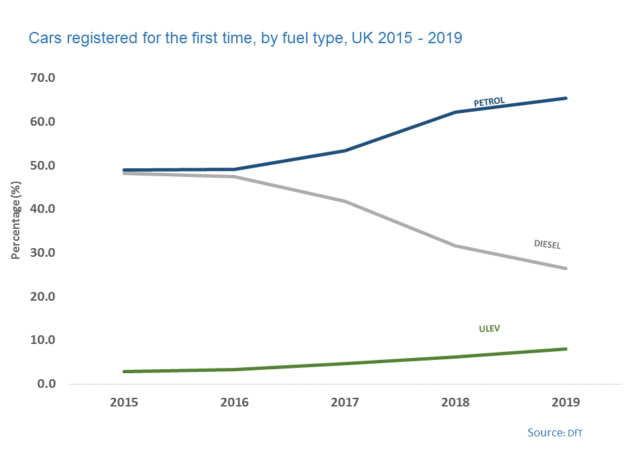

Current government statistics on uptake refer to ultra low emission vehicles (ULEV). ULEVs are those that use low carbon technologies and have tailpipe emissions of less than 75g of CO2 per kilometre. Vehicle licensing statistics show the number of ULEVs is growing, predominantly through the sale of battery electric vehicles (BEV), sometimes referred to as pure electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV). At the end of September 2020 there were more than 164,100 licensed BEVs and over 373,600 PHEV cars in the UK. Though this growth is encouraging, new petrol car sales are rising at a higher rate than ULEVs and the total number accounts for only 0.5% of licensed vehicles in the UK.

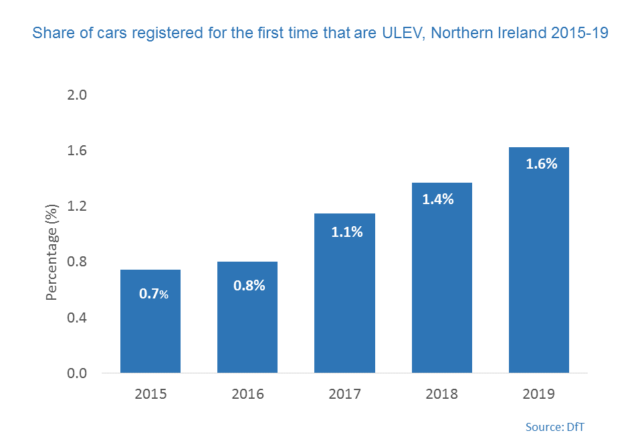

Of the approximately 1.2 million licensed vehicles in Northern Ireland, just over 3,600 were ULEVs (0.3%).While this number is low, the proportion of all new ULEV being registered each year has risen from 0.7% in 2015 to 1.6% in 2019.

Towards zero emission vehicles

The Government has taken decisive action, announcing there will be no new petrol or diesel cars and vans sold from 2030, with the sale of new hybrid vehicles banned from 2035. The Road to Zero Strategy outlines how the UK Government will support the transition to zero emission including a range of fiscal measures, designed to improve infrastructure and make the purchasing of ULEVs more attractive. For example,

- Grants for charge-point installation at residences and workplaces are available via the Workplace Charging Scheme and the Electric Vehicle Homecharge Scheme.

- On-street Residential Charge point Scheme (ORCS) provides grant funding to local authorities, covering 75 per cent of the cost of installing on-street charging points.

- The Plug-in vehicle grant scheme (the PIVG scheme) provides a grant of up to £3000 to incentivise the purchase of new ULEV.

- Reduced Benefit-in-Kind (BiK) tax. BiK tax is paid on non-salary benefits included within an employee’s remuneration package. For company cars, BiK tax bands are calculated on the basis of CO2 emissions. Vehicles producing zero tailpipe emissions incur no BiK tax, rising to 1% from 2021-22 and 2% from 2022-23.

- Vehicle Excise Duty (VED) exemption. An annual tax which is calculated on the basis of a vehicle’s CO2 emissions. Vehicles producing zero tailpipe emissions pay no VED.

Reducing emissions from the tailpipe is only one of the challenges if we are to have truly zero emission vehicles. There are questions around the carbon intensity of the grid fuelling the vehicles as well as issues around the sustainability of the entire battery lifecycle, from construction to decommissioning that need to be addressed. There are advancements to be made on these fronts, although research does show that even with the current grid and manufacturing processes, emissions from a conventional car are almost 3 times higher than a BEV over the entire lifecycle of the vehicle.

This transition towards zero emission road transport will be costly and may require some controversial policy interventions. The CCC estimates it will cost £11.4 billion of average annual investment over the next 30 years. This includes public and private sector investment as well as the money consumers invest in cars. It will also have an impact on tax revenues. Peter Foster, in the Financial Times on March 1 2021, noted “Treasury will need to find a way to recoup the £37bn a year it currently secures from carbon taxes, mostly fuel duty and vehicle excise duty.” Suggesting the main contenders for replacing that revenue are “some combination of per-mile road-pricing and congestion charging”.[1]

Key barriers to ULEV uptake

Research on barriers to ULEV uptake in the UK points to four key barriers: upfront price; charging infrastructure; range anxiety; and lack of vehicle choice. Research into people’s attitudes towards electric cars, as part of Northern Ireland’s Continuous Household Survey 2019/20 supports these broader findings with 64% of respondents identifying ‘purchase price’, 49% identifying the ‘need to recharge your vehicle’ and 37% identifying ‘vehicle range from one charge’ as the main reasons discouraging them from purchasing an ULEV. On a more positive note, ‘Low overall running costs’ (cited by 53% of respondents) and purchasing grants (51%) were the things that would encourage ULEV purchases.

Changing perceptions

It could be argued that these barriers may be more to do with perception than fact and that if more information was available to potential purchasers their views could change. For example, it is true that ULEVs are more expensive, with the average cost roughly £10,000 more than its conventional counterpart. However, research suggests that the price premium, can often be offset by lower running, maintenance and taxation costs, and that in fact the ‘lifetime cost’ of a ULEV is already lower than an equivalent petrol vehicle.

Investment by the UK Government and the private sector has seen the UK’s public charging network expand and as this continues this becomes less of a barrier. According to ZAP MAP, the UK now has over 38,000 public chargepoints across more than 14,000 locations, including almost 10,000 rapid charging points. This is more than double the number of charge points available in 2016. As a region only the Isle of Man and Channel Islands have fewer charge points than Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland’s public charging network is called the ecarni network and consists of 334 charge points, including 14 rapid charge points near key routes . ecarni was founded in 2011 by the former Departments for Regional Development (DRD) and Environment (DoE) with funding from the Plugged-in Places scheme. It was set-up to promote the uptake of electric vehicles in NI and roll out a network of charging points. In 2015, the running of the network was awarded to the Electricity Supply Board (ESB) which continues to operate both the NI and ROI networks.

Consumer confidence in the availability of charging infrastructure will be critical in encouraging people to transition to ULEV. At this point we don’t know what people’s experiences and perceptions of the NI charging network are and this is an area which would warrant further research. The CCC suggest it will require significant development, estimating it may require between 30 to 35 public rapid chargers on major roads, and 800 to 950 public top-up chargers by 2030.

Range anxiety is another key barrier, this explains why PHEVs, which have that backup of petrol or diesel, have been much more popular than BEVs in many countries including the UK. But how many people are aware of the advancements made in range over the last decade? “The driving range of BEVs has increased from approximately 80-120 miles in 2010, to an average of 194 miles in 2020”. Range is increasing but ultimately cost will be a factor and manufacturers will aim to maintain a price level. Indeed, BEVs with a driving range of greater than 400 miles already exist today, but these vehicles, from manufacturers such as Tesla are within a price range that is likely out of reach for the average buyer.

Outlook for EV

Analysis by industry experts suggests we are at a tipping point with regards to uptake of ULEV. KPMG suggest the next couple of years will see the number of ULEV rise significantly and that the government targets are not unrealistic. This will be driven by the increasing supply of affordable models, and greater levels of choice. KPMG does point out that continued investment in charging infrastructure is necessary to combat ‘perceived range anxiety’.

ULEV policy

Much of what has been discussed in this blog article has evolved around current and future UK government policy that will have a significant impact on the ULEV market in Northern Ireland:

- Tax and vehicle standards are set at a UK level.

- The Office for Low Emission Vehicles (OLEV) operates most of the financial incentive schemes, such as the Plug-in Car Grant scheme.

- The Road to Zero is a UK-wide strategy and includes measures that will apply to the whole of the UK.

- Supply-side measures to support ULEV manufacturers are covered by UK-wide policy (e.g. the Industrial Strategy Automotive Sector Deal).

The CCC has laid out the areas where the NI Executive can exercise its devolved powers to support the transition to zero emission vehicles:

- Operating and promoting specific schemes that have secured funding from the UK government, such as the ecarni scheme.

- Identifying and pursuing opportunities to secure funding from UK-wide funds for ULEV infrastructure in Northern Ireland.

- Providing leadership by decarbonising the public sector and bus fleets.

- Use of the infrastructure budget on electric vehicle charging infrastructure. The e-car public charge point network in the North is owned, operated and maintained by the Electricity Supply Board (ESB).

- Setting targets for ULEV sales that go beyond those laid out in the Road to Zero Strategy; and

- Taking steps to address non-financial barriers for electric vehicles, including local measures such as parking, use of priority lanes, and public awareness campaigns.

Conclusion

The future of driving in Northern Ireland will be fuelled by electricity. The question for drivers is no longer a matter of will I transition to electric vehicles, but when will I make that transition. While the Government has established a regulatory environment to push the transition, car manufacturers are beginning to attract consumers, albeit slowly, with a range of new vehicles at increasingly competitive prices. It appears that all that is needed is more information about the benefits of ULEV and the infrastructure to accommodate it.

The NI Assembly Infrastructure Committee has put out a survey to ask the people of Northern Ireland what they’re views are on a future of driving fuelled by electricity. The Committee wants to hear from everyone, whether or not you own, or have owned, an ecar in the past, whether you support this policy or whether you are completely against it. These views will be considered by the Committee for Infrastructure in its inquiry looking at what it will take to decarbonise road transport in Northern Ireland and will help form recommendations to the Minister.

[1] Price of going net zero about to be driven home for Britons, Peter Foster in the Financial Times, Brighton, March 1 2021 (Subscription required)