This blog article focuses on key UK Government, Northern Ireland Executive and Departmental initiatives which are currently in place to address the digital divide in Northern Ireland (NI). Following on from the previous blog post initially addressing this topic, two further key areas to address are: infrastructural issues inhibiting some individuals’ access to digital technologies; and, digital skill gaps impeding some individuals’ ability to carry out basic digital tasks.

Context

It must be noted that there was difficulty in gathering information upon the initiatives which are operating to close the digital divide in NI. This was because policies often involve a mixture of public and private funding, and legislative powers on telecommunications are a reserved matter under prevailing devolution; thus remaining within the control of the UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). However, NI’s Department for the Economy (DfE) has limited powers under the Communications Act 2003, when there is evidence of market failure. Those limited DfE powers also enable the Department to provide grants to those concerned with ‘the provision of electronic communications networks and electronic communications or improving the extent, quality and reliability of such networks or services’.

Current projects

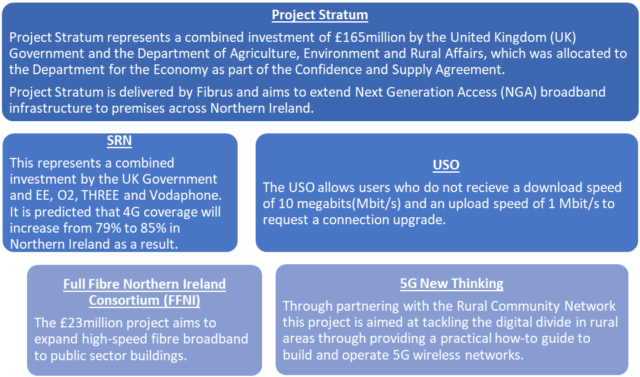

Assessing the current projects in place, they have a strong focus on addressing key infrastructural challenges facing NI, namely broadband and mobile coverage. Those projects now operating include Project Stratum, Shared Rural Network (SRN) and the Universal Service Obligation (USO). A number of smaller scale projects include the Full Fibre Northern Ireland Consortium and 5G New Thinking (Figure 1).

Addressing the digital skills gap

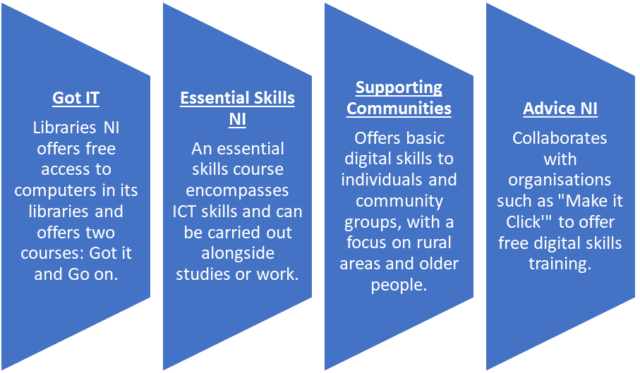

In terms of addressing NI’s existing digital skills gap, it is unclear if the NI Executive has a dedicated strategy in place. Go ON NI is recognised as the Flagship Initiative of the NI Executive (digital skills is a devolved matter). It can be seen that Go ON NI is a website that connects the user to projects and training opportunities which are aimed at developing their digital skills. Examples of such projects can be seen in Figure 2.

Examining Go ON NI in further detail, it can be seen that the initiative is a resource for those who are already able to get online and use these digital platforms. However, there is no active dedicated government strategy to engage those who currently are offline, cannot access or are unable to use the internet or technological devices and therefore cannot access the Go ON NI platform.

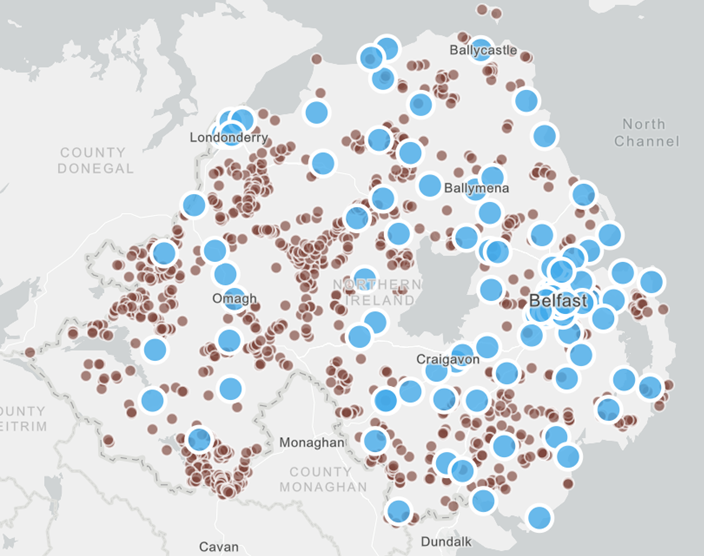

Furthermore, exploring the tool Free Internet Access on Go ON NI, it can be seen there is a clear concentration of online centres in the Belfast area. The spatial distribution of resources is reinforced when comparing the location of library services across NI. Figure 3 (below) shows the location of libraries across NI versus the number of postcode areas which receive less than the Universal Service Obligation (USO). Using the filter function on the interactive map to select ‘100%’ of those postcode areas which do not receive the USO of broadband speed, it can be seen that there are clear clusters of areas located in South East and North West of County Fermanagh and in North East and North West of County Omagh.

Closer examination of the clusters in Figure 3 highlights the mapped areas are primarily located in rural locations. However, some also are located in towns and around urban centres. This is important to note, as although Project Stratum is focused on delivering NGA broadband across Northern Ireland there should be a strong focus on rural areas. This is because the expansion of rural broadband must develop simultaneously with urban rollout to avoid a ‘two-speed economy and two-speed societies‘.

Superimposing the location of library services onto Figure 3, it can be seen that the poor broadband connectivity clusters in NI are not located near a library, as is highlighted in Figure 4 below. This is significant because the next available option for those with poor connectivity at home is a library, which Figure 4 demonstrates is not easily accessible. This is further compounded when the individual does not have access to personal transport. For example, public transport infrastructure is not readily available across many remoter rural regions in NI, so residents living in these areas are reliant on services such as Dial-A-Lift. This is a critical point to note as Libraries NI is a key partner in delivering programmes falling under Go ON NI and those most likely to have zero to little digital skills, i.e. those who are: socially excluded; retired or older people; disabled; located in rural areas or other areas with poor connectivity, are at even more risk of digital exclusion because core services are not easily accessible to them.

Potential solutions to closing the digital divide

The importance placed by the NI Executive upon digital skills, accessing digital services and infrastructure can clearly be seen through the Digital Transformation Programme and the inclusion of these topics in the Rural Policy Framework and The Skills Strategy. It now remains to be seen as to how the Draft Executive Budget 2022-25 will allocate existing funding, following on from the UK Chancellor’s Autumn Budget 2022-25 on 27 October 2021. Drawing upon the Department for the Economy’s consultation document to achieve a 10x Economy introduced in May 2021, it specifies that a specific NI Digital Skills Action Plan needs to be developed, stating:

The social and economic necessity of this could not have been more starkly portrayed than through the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. It has highlighted the growing digital divide… and has exposed the increasingly essential presence of digital skills, and digital access, in our society and labour market. It is incumbent upon Government to empower individuals to take the social, and labour market opportunities that digital skills afford.

In respect to the Autumn budget, and subsequent devolved budget of NI, it can be seen that there is a focus upon investing in digital services. For example, £300,000 has been allocated to the Glens Digital Hub in Cushendall. The remaining funding from the £400 million New Deal remains under consideration, however, it has been proposed that skills development should be an area of investment. This is no more apparent when it is estimated that 90% of new jobs will now require digital skills, with 72% of employers requiring basic digital skills as a mandatory requirement. With this framework, it can be seen there is an opportunity for the NI executive and its departments to consider investing in boosting the digital skills of the NI population with those funds which are not allocated to serve other purposes.

Therefore, a strong financial commitment and opportunity to close NI’s digital divide is evidenced by the noted Executive policy commitments and related investment. However, the digital divide cannot be fully addressed by policies purely focused on broadband infrastructure, when multiple causes evidencing digital exclusion exist. For example, The Digital Citizen Project was successful in addressing the issues of both broadband access and digital skills through libraries delivering learning opportunities. This project illustrates how both policy objectives could be achieved. Furthermore, the importance of long-term tailored support is evidenced by the finding that 26% of beginners surveyed in 2017 did not use their new digital skills without ongoing support.

Similarly, schemes such as Superfast Cornwall have demonstrated the benefits of a more targeted, collaborative, long-term approach. The Superfast Cornwall Digital Inclusion scheme and the rollout of superfast broadband since 2011 have more than halved the number of those individuals who were offline. It boosted 3,000 people’s online skills and connected 90% of premises to a fibre-based network. In the context of NI, it could be worth examining (at devolved and local government levels) how future projects in NI could adopt a similar framework to the Digital Citizen Project or Superfast Cornwall. Such examination, however, would need to be targeted appropriately for the unique circumstances of NI. These circumstances are currently under-researched and as such, future research in this area should go beyond broadband speed mapping, and consider the causes and the needs of digitally excluded groups in NI.

Conclusion

Examining key NI policies currently tackling the digital divide has shown that there is strong emphasis on infrastructural rollout and digital skill improvement. However, concerns remain around the issue of accessing digital technologies and thereby attending digital skill courses on offer.

In sum, while the Executive’s future NI economic vision has placed a strong emphasis on the importance of digital skills, there is a need to ensure that future policies aimed at tackling the digital divide better align. This is not only critical in respect to the future direction of the NI economy, but also in order to ensure that those most at risk of digital exclusion are not left even further behind.