Sign Language (Northern Ireland) Bill 2025

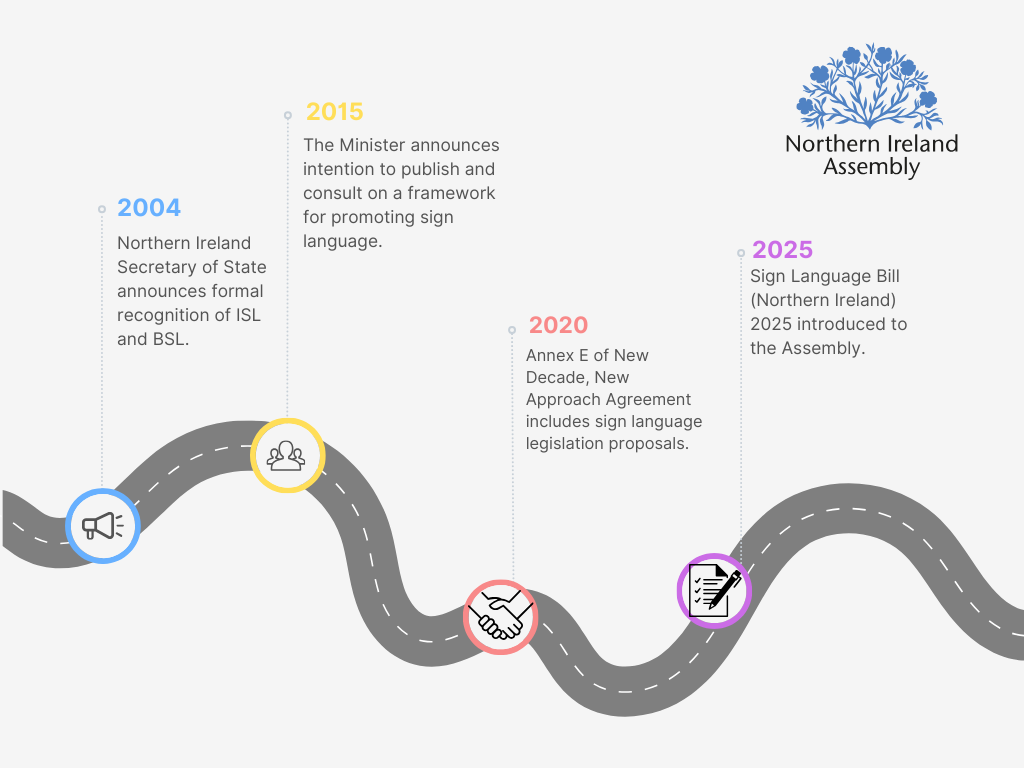

A Sign Language Bill was introduced to the Northern Ireland Assembly on 10 February 2025. This blog post provides stakeholders and elected representatives with an overview of the Bill, comparing it with sign language legislation elsewhere. This post is a summary of a bill paper by the Assembly Research and Information Service. Signed translations of the key points of this paper can be found below, in both Irish Sign Language (ISL) and British Sign Languages (BSL).

The last to Act

Before the Bill was introduced, Northern Ireland was one of the last jurisdictions within these islands without legal protections for its sign languages. Yet, Article 30 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), ratified by the UK in 2009, stated that:

…persons with disabilities shall be entitled, on an equal basis with others, to recognition and support of their specific cultural and linguistic identity, including sign languages and deaf culture.

A British Sign Language (BSL) Act received Royal Assent on 28 April 2022. This Act did not include Northern Ireland because Irish Sign Language was not in scope of the GB legislation. In Ireland, the Irish Sign Language (ISL) Act was passed in December 2017 and the BSL (Scotland) Act received royal assent in October 2015. In May 2024, a Member of the Senedd won a ballot to introduce a British Sign Language (BSL) (Wales) Bill. The Welsh Bill seeks to expand the protections offered in the British Sign Language (BSL) Act 2022, with an aim to establish a BSL language commissioner, with powers similar to the Welsh language commissioner. In Northern Ireland, a Sign Language Bill was introduced to the Assembly on 10 February 2025 and its second stage debate was on 18 February. At the time of writing, Committee Stage had commenced and was extended to a limit of February 2026 to allow time for sign language interpretation and translation of proceedings.

The Bill is what can be described as a framework Bill and enables the Department for Communities (DfC) to pass delegated legislation through regulations by resolution of the Assembly. This means many of the potential policy implications that may result from the Bill are as yet unknown. Given the cross-cutting nature of some of the clauses, including a so-called Henry VIII clause, careful consideration of each clause as well as close examination of any assumptions about sign languages are required.

No universal sign language

There is no universal sign language. British Sign Language (BSL) and Irish Sign Language (ISL) are distinct languages and each has its own sentence structure and grammar, and differs from spoken English and Irish. Variances between different regions complicates provision of services. This requires consideration when examining plans for local communication services.

Planning resources

We don’t know with certainty the number of different sign language users in Northern Ireland. According to DfC:

…BSL is the first or preferred language of communication of approximately 3,500 members of the Deaf population of Northern Ireland while approximately 1,500 use ISL.

According to the Department of Health, there are approximately 8,000 sign language users in Northern Ireland. The Continuous Household Survey in 2013/14 reported that 9% of adults in Northern Ireland could use a sign language, with 8% using BSL and 1% using ISL. Deaf community groups in Northern Ireland called for the 2021 census to capture an accurate figure for the number of people in Northern Ireland who use BSL or ISL. Almost 6% (109,500) of the population of Northern Ireland reported deafness or partial hearing loss and 539 reported BSL as their main language, while 90 reported ISL. The census was translated into ISL and BSL in 2021. But the implications of asking respondents to choose their ‘main language’ and ‘household language’ has been critiqued by academics in England, as this phrasing does not capture those who regularly use more than one language. This is not just an issue for Northern Ireland. In Scotland’s National Plan for British Sign Language, the first of its 70 actions was to:

Develop and test a new question on the use of BSL in Scotland for potential inclusion in Scotland’s Census 2021. This will give us a more accurate profile of Scotland’s BSL users.

According to Scotland’s 2021 census results, around 13,000 people used British Sign Language at home in Scotland, which is about 0.2% of the population.

Equal access

As the Equality Act 2010 does not form part of the law in Northern Ireland, most protections for the local deaf community come under the Disability Discrimination Act 1995. In disability and equality legislation, provision of ‘reasonable adjustments’ for sign language users often means communication services, such as an interpreter. Accessing ‘reasonable adjustments’ means identifying as disabled. Many in the deaf community prefer legal recognition as an indigenous cultural-linguistic minority, with legislation to protect and promote deaf culture. The Northern Ireland sign language Bill attempts to do this, with Clause 1 recognising both ISL and BSL equally. Research persistently suggests that the provision of ‘reasonable adjustments’, such as sign language interpreters to support access to health, education and employment, is still lacking, despite disability legislation. A House of Commons Early Day motion in 2013 suggested this was due to a lack of public understanding of sign languages and qualified interpreters. Rosie Ayling Ellis’ win on Strictly Come Dancing may have raised awareness of deaf culture, but witnesses at a Communities Committee hearing in March 2021 described the difficulties of getting local support. Many of the organisations supporting deaf people operate on a UK-wide basis and are headquartered outside of Northern Ireland.

What does sign language legislation include?

Table 1 provides a comparison of the GB, Scottish and Irish Acts, with the Northern Ireland Bill.

| Feature | Northern Ireland Sign Language Bill 2025 | British Sign Language Act 2022 (England & Wales) | Irish Sign Language Act 2017 | British Sign Language (Scotland) Act 2015 |

| Recognition and Aims | Recognises BSL and ISL as languages of Northern Ireland, granting them equal status; aims to promote use and understanding | Recognises BSL as a language of England, Wales, and Scotland | Recognises ISL; grants ISL users the right to use their language with public bodies | Focuses on promoting the use and understanding of BSL |

| Languages | BSL and ISL | BSL | ISL | BSL |

| Responsibility | Department for Communities | Secretary of State | Minister for Justice and Equality | Scottish Ministers |

| Scope and Implementation | Introduces ‘prescribed organisations’ with accessibility duties | Primarily requires the Secretary of State to report on government departments’ BSL promotion efforts and issue guidance | Addresses legal proceedings, educational support for deaf children | Mandates Scottish Ministers to prepare and publish national plans for BSL and requires certain authorities to develop their own BSL plans |

| Public Body Duties | ‘Prescribed organisations’ must take reasonable steps to ensure their information and services are as accessible to individuals in the deaf community as they are to others, at no extra cost. | Relies on Secretary of State to report on promotional activities | Mandates public bodies to provide ISL interpretation | Requires listed authorities to publish their Authority Plans in British Sign Language |

| Use in Legal Proceedings | Not specifically mentioned in Bill | Not specifically mentioned in Act | Explicitly allowed (Section 4(1)) | Not specifically mentioned in Act |

| Education Provisions | DfC to promote availability of sign language classes | Not specifically mentioned | Detailed provisions for ISL classes, support in schools, and teacher training (Section 5, Education Act 1998) | Included in the National Plan |

| Broadcasting | Not specifically mentioned | Not specifically mentioned | Principles of equality, dignity, and respect in ISL programming (Section 8, Broadcasting Act 2009) | Included in the National Plan |

| Support for Access (Cultural/Arts Events) | Not specifically mentioned | Not specifically mentioned | Yes (Section 9) | Included in the National Plan |

| Community involvement and consultation | The Department for Communities must consult with prescribed organisations and deaf community representatives when devising or reviewing guidance. Similarly, before laying regulations, the Department must consult those on whom functions are to be conferred and at least one person or group acting on behalf of the deaf community. | Not explicitly mentioned | Not explicitly mentioned | Requires Scottish Ministers to consult with persons who use BSL and those who represent BSL users when preparing a National Plan. The listed authorities must publish and consult on a draft of their Authority Plan, considering any representations received. |

| Guidance, Reporting, and Accountability | Department for Communities to issue guidance and publish 5-yearly reports assessing the impact of the legislation | Secretary of State to report on government departments’ promotion and facilitation of BSL | Minister to report on the Act every 5 years | Mandates progress reports to be presented before the Scottish Parliament |

| Accreditation and Standards | Includes a scheme for accrediting teachers and interpreters of BSL and ISL | Not explicitly addressed | Accreditation scheme for ISL interpreters | Not explicitly addressed in provided text |

| Addressing Different Language Forms | Explicitly includes both visual and tactile forms of BSL and ISL | Not explicitly addressed | Not explicitly addressed | Refers to both visual and tactile forms of BSL, but specifies that the publication of national plans should be in visual BSL only |

| Commencement | Phased implementation | Day after Royal Assent (Section 4(3)) | Phased implementation within 3 years (Section 11(2))

|

Phased implementation |

Table 1 Comparison of sign language legislation

Issues for consideration

Communication services

There are 39 registered interpreters in Northern Ireland. These interpreters work across health, education, justice and communities. A Health and Social Care Board (HSCB) review in 2019, recommended the development of a ‘regional standardised model of service provision’. During the COVID-19 pandemic, video relay services were jointly funded by the Department of Health and DfC. A 2021 HSCB evaluation reported that:

Between April 2020 and March 2021 more than 8,000 […] interactions supported by VRS and VRI have occurred between HSC staff and Deaf people. […] in 2018/19 sign language interpreters provided 3,573 face to face interpreting assignments in HSC settings across Northern Ireland.

Witnesses at a Communities Committee meeting on 5 March 2021 described how local users must access different video relay service (VRS) applications to connect with different public services. In Scotland, one VRS system is used for all services in the jurisdiction.

Early Years

Approximately 90-95% of deaf children are born to hearing parents with limited knowledge of sign language. A lack of language development from birth may affect a child’s development. Researchers suggest that deaf children born to deaf parents perform better academically than deaf children of hearing parents. To improve the outcomes of deaf children, DfC’s Sign Language Framework in 2016 highlighted the importance of offering free sign language classes in family friendly teaching formats. Clause 2 of the Bill describes the provision of classes, but does not specify the cost for attendees. DfC commissioned Queen’s University Belfast academics to review sign language classes for families of deaf children in March 2025.

Education

In 2024, the Consortium for Research in Deaf Education (CRIDE), estimated that 1,603 deaf children attend schools here. In 2016, DfC’s Sign Language Framework noted:

No hearing community would tolerate their children being educated solely by those who cannot communicate with or understand their children. Yet Deaf children with normal cognitive ability are expected to function in just this environment.

This requires adequate teacher training resource. The Bill does not specify the provision of teachers of deaf children (ToDs). The accreditation of teachers of sign language classes, described in Clause 8 of the Bill, differs from the mandatory qualifications of ToDs. Special educational needs are overseen by the Education Authority and are the responsibility of the Department of Education and represented on the DfC-led Sign Language Partnership Group. Although the Sign Language Bill provides for the recognition and promotion of BSL/ISL it does so while preserving the architecture of disability legislation and any other established rights of individuals in the deaf community. There have been recent court cases in Ireland and Scotland concerning the provision of suitably qualified sign language teachers and interpreters in schools. Both Scottish and Irish Bills fell during initial attempts to pass sign language legislation in part due to concerns about the provision of qualified teachers and interpreters. These resources may be difficult to plan for in Northern Ireland, given the lack of data about the size of the sign language community.

Higher and Further Education

DfC’s Sign Language Framework highlighted a lack of supply of ISL/BSL teachers qualifying to meet the demand for sign language classes and ISL/BSL interpreters. In February 2024, the Minister for Communities set out proposals to increase the number of interpreters and on 6 February 2025, DfC officials described how the Department provided funding to:

…support a BSL/ISL interpreter training programme that is to be delivered by the Foyle Deaf Association, and successful students are due to register as accredited interpreters in the near future. In addition, the Department has developed, provided funding for and launched a two-year Master of Arts (MA) in sign language interpreting at Queen’s University Belfast, comprising BSL and ISL students, both deaf and hard of hearing. That will provide an additional increase in capacity to address the current pressures for interpreters and contribute to the expected increase in demand arising from the legislation.

Employment

DfC’s Sign Language Framework noted:

Deaf Sign Languages users experience higher levels of unemployment than their hearing peers while there are considerably higher levels of Deaf young adults not in education, employment or training (NEET).

The Sign Language Framework recommended:

Deaf friendly work fairs, Deaf Hubs, employer Deaf awareness training and work placements and IT training to improve employability.

Access to Work is a scheme of funding support ‘to overcome practical problems caused by disability’. In 2019/20, 80 people listing hearing as a disability used the Access to Work scheme in Northern Ireland. At a Communities Committee meeting on 5 March 2021, deaf community members raised concerns about the difficulties of using this programme.

Justice

Recent research on the implementation of Article 13 of the UNCRPD in Northern Ireland, evidenced a lack of high-quality interpretation, deaf awareness training, guidance on available supports and accessible information as barriers to the justice system for the local deaf community.

Reporting

Reporting of progress is mentioned in the Sign Language Bill, as well as the ISL Act in Ireland and the BSL Acts for Great Britain and Scotland. In Northern Ireland, Clause 9 in the Sign Language Bill sets out an a five-yearly reporting cycle. In the second stage debate, Members asked the Communities Minister if an initially shorter reporting cycle would be considered. A Westminster Hall debate following the first-year review of the enactment of its BSL Act, suggested that the effectiveness of sign language legislation depends not only on its implementation but also on continuous monitoring and improvement. At the second stage debate, the Minister suggested he would consider a shorter reporting cycle.

Nothing about us, without us

In Great Britain, a non-statutory board of BSL users advise the Department of Work and Pensions. DfC’s Disability Strategy Expert Advisory Panel recommended including members of deaf communities in the design of data collection and evaluation reports. The DfC leads a Sign Language Partnership Group, that includes Departmental officials as well as representatives from the deaf community. This group is not explicitly mentioned in the Bill. Several clauses require the Department to consider representation from at least one member of the deaf community. Given there are two sign languages to be equally protected and promoted in the Bill, this approach may require further consideration.